What's Good

There was nothing unfamiliar about those songs——they opened a window onto where you were living already in your head. They were exactly what you were interested in, exactly what you’d been looking for——exactly what was needed. Who wouldn’t wanna be in the middle of that scene with Cecil and his new piece and the sailor and the bloodstains on the carpet and an arm full of speed and someone sucking on your ding dong? Is it any less than you deserve? Who doesn’t want and expect the freedom to fuck and dress as he or she or he-she pleases? Who wouldn’t play guitar like on “What Goes On,” if you could play the guitar? (Okay, every other guitar player, I guess, but screw them. That’s how I’d do it.) The surprising thing about the songs was their perfect inevitability, both the sound of them and what they were “about.” It’s like they were finally letting go of the good stuff, the real stuff——you know, not one part good stuff to four parts bullshit but everyone in the band doing the perfect thing——you never knew you could get it so pure. Every note the Velvets played was exactly what you wanted——your own desires coming back to you. They were the musical version of the question Burroughs used to ask: Wouldn’t you?

People are always describing Lou Reed as the Dark Prince of this or that, as the man who broke the taboos and who wrote about heroin when the Beatles were writing about, I dunno, the circus. But those are adult taboos. What kid is shocked by these things? The only shocking thing about those songs is that they described drug abuse and S&M and homosexuality and transexuality and found nothing shocking there, and they allowed you to admit that you, too, found nothing shocking there. Why would you? You’re a kid, you take the world as it comes. You’re putting the world together for yourself——what do you stand for? Who wouldn’t want to be the kind of person who took the humanity of these people and the intensity of their lives with immediate, unblinking acceptance, as a given? Lou didn’t explain his world and you didn’t need him to. He allowed his subjects and you the dignity of not explaining his world and thereby made it yours.

*

Maybe twenty-five years later, I caught myself standing stopped in my tracks in the middle of a room in San Francisco while a CD played, and I overheard myself say, “How many times can a person listen to ‘What Goes On’ in his life?” By then I had the usual mixed feelings about Lou Reed, best captured in the single syllable used as currency by those of us who’ve carried a torch for him for all these years: “Lou.”

If you’re reading this, you know all about it. (If you don’t, or you want to remind yourself of what was so great about him after the Velvets, go listen to some of his solo stuff, not just “Walk on the Wild Side” but also Coney Island Baby and “Temporary Thing” and “High in the City” and “Romeo Had Juliette” and “Halloween Parade,” and the monologue on “Street Hassle” and the wave of fear that blows across “Perfect Day” like a cloud moving across the sun, and the way he drops taped conversations into “Kicks” and “All Through the Night,” and the precision guitars on “What’s Good,” and the joyful leads he squeezes out on “I Love You, Suzanne” and “Outside,” and the serrated roar he lets rip on the Take No Prisoners version of “Satellite of Love,” and his guitar part on Antony’s “Fistful of Love,” which I’d trade for everything else he did in the last 20 years.) He made records so bad you don’t even want them in the house, but nothing’s made a dent in his cool. He was bigger than his songs. Maybe his real achievement was his aura. Couple of years ago I was talking to June, my girlfriend, bitching about getting old, and I said something like “Nobody’s cool past fifty.” And she said, “Look at Lou Reed: who’s cooler than him?” The answer was no one, and the proof was that he’s the one who’d first sprung to her mind.

Speaking of getting old, I find that now as I look back over these songs, what I get from them is a certain feeling for the world, a canny, street-level humanity, a basic New York understanding that life is for the living and worth it, a kind of twinkle that reminds me to be of good cheer. What’s good? Lou Reed. Lou Reed was one of the good things about life. Is.

*

A long time ago, Andrew Klimeyk wrote me in a letter that the VU songs were his hymns. He said he could imagine a world without airplanes or telephones, but he couldn’t imagine a world without “Pale Blue Eyes.” This morning I took the train over the Williamsburg Bridge——I hadn’t been home in a couple of weeks because I had someone staying at my place——and I looked up from what I was reading and saw that suddenly all the trees tossing in the wind were red and brown and yellow——there wasn’t a green leaf in sight. It’s autumn and that’s that. The other day Doug Morgan wrote this to me: “His passing lends truth to the cliché ‘Time heals all wounds.’ I even forgive him Rock n Roll Animal, whatever that is. I think the VU were the ‘perfect accident’: if you see something, say something, because you’re never coming back.”

So long, Lou.

Sha la la, man.

Download:

"What Goes On" mp3

by The Velvet Underground, 1969.

available on 1969: The Velvet Underground Live

"Coney Island Baby" (alternate version) mp3

by Lou Reed, 1975.

available on Coney Island Baby

"Street Hassle" mp3

by Lou Reed, 1978.

available on Street Hassle"I Remember You" mp3

by Lou Reed, 1986.

available on Mistrial"What's Good" mp3

by Lou Reed, 1992.

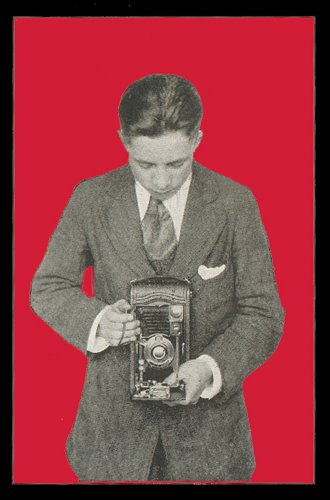

available on Magic And Losstop photo: Andy Warhol, Screen Test: Lou Reed, 1966.

other photo: by Michael Zagaris, 1974.

Andy Warhol. Screen Test: Lou Reed (1966).

Andy Warhol. Screen Test: Lou Reed (1966).

Andy Warhol. Screen Test: Lou Reed (1966).

6 comments:

Great piece, Mike. Been listening to all the VU versions, outtakes, and even Nico's solo work. Reassuring stuff, as you indicate. Thanks.

It's supernatural, how that stuff never gets old.

Thank you, Vincent.

As a huge fan of Nico's solo work up til about 1979, I hadn't really followed Lou's separate career too closely, was more into John Cale and the less outrageous knockoffs...it was when Velvet Goldmine came out that I realized how subliminal, how insidious, and how seductive Lou Reed's work had been, luminous threads running through the 70's, 80's, even 90's....it seems so obvious now, but there was so much else going on at the time, punk, new wave, ska, etc. Then later, my musical tastes went off in an entirely different direction but I found myself humming 'Satellite of Love' at the oddest times. Suffice to say that Lou Reed was an avatar, an icon and a man far ahead of his peer group, if not of his time; I'd say he was very much OF his time. And that's not a bad thing.

Lou was real good Mono in a Stereo world

No one needs to forgive Rock n Roll Animal. It is what it is and that is a primer in what 1970s live hard rock SHOULD have been.

Post a Comment