Come And Found You Gone

by Pete Simonelli

Now this here’s the first piece I learned how to play when I was a little boy: it’s called the "Big Fat Mama with the Meat Shakin’ On Her Bone.”

So begins Devil Down Records’ inaugural release, Come and Found You Gone: Mississippi Fred McDowell: The Bill Ferris Recordings. Immediately, we are transported back to a night in August, 1967, when Blues scholar Bill Ferris brought together McDowell, friend and cohort, Napoleon Strickland, and Fred’s wife, Annie Mae McDowell, into the home of an “unidentified musician” for a night of recording, drinking, and good, loose fun.

Then again, one could almost call the few opening minutes of this gathering breezy. Three of the first four tracks feature easily identifiable songs of McDowell and his grab bag of traditional tunes, including “Big Fat Mama,” “Shake ‘em On Down” and “Baby Please Don’t Go,” respectively. They come and go with a swift familiarity that McDowell seems almost eager to get behind him. Not until we’re introduced to the fourth track, “Find My Suitcase,” does the mood shift into something a little more focused, if not truly demonstrative of McDowell’s usual prowess and finesse as a bottleneck guitar player. He had always stressed his need for a “feeling” to accompany his playing and singing, and, to my ears, I can’t say that I hear that special confluence of the emotional and the physical until he sort of cat-walks into “Find My Suitcase.” The vamp starts off in a slow, slithering manner until, just a few bars in, the combination of melody and rhythm seems to leap into his voice and send us, the listeners, into a grinning fit of head-bobbing (in my case, also hand-clapping) joy. Up to this point it’s easily the most fluid and loaded number yet. It sounds as though he’s warmed up now; perhaps the whiskey’s starting to hit, and his “feeling” arrives in the amalgamated and masterful way any fan of Mississippi Fred McDowell has come to know and love.

He performs solo throughout the first seven numbers before our “unidentified musician” takes the vocal on “Dream I Went to the UN.” Strickland follows with a hot solo harp piece called “The Boogie.” McDowell then accompanies the homeowner on a wandering version of “Little Red Rooster” before we move right into the spiritual mood of the evening, beginning with “Get Right Church,” which is far and away the most somber but moving moment on the CD. McDowell delivers a weary and sad opening, but the others, as though prompted by the tone, take up the call and deliver a mesmerized, "slain in the spirit” performance. The melody is ominous and fearful, indicative of some great underlying menace that can only be relieved by a collective rising of voice and faith. It also instigates a pivotal shift in the entire recording: only now is everyone truly involved; they are engaged in a purpose. The tenor of the evening has switched to a collective outpouring of voices and emotions that hadn’t yet been exposed. Now we hear Mae’s beautiful punctuations as well as Strickland’s and the homeowner’s presence driving the overall performances into a realized recording. It’s not that any fun is gone. It’s just that they’re all in tune with one another, and the ensuing tracks that take us into the end of Come And Found You Gone find a special accent and grace. A track called “Dialogue” (No. 13) gives the recording some additional potency. It features some testy, marital back-and-forth between Mae and Fred that the homeowner has to subdue with a very diplomatic “You’re singing fine” to Mae. It signifies a high point in the group’s general demeanor. They’re all ready, animated--- this is a party after all--- and the banter flying about the room is quick and sharp. The track keeps rolling on for another minute and a half while Fred plucks and tunes, getting ready for the next number. But Mae isn’t giving in. She ribs and taunts Fred like she wants some of the spotlight, too. It’s a great little moment in the CD that reinforces the sense of being in a very particular time and place.

Ferris’s intention was clear: to capture a great musician in a casual, down-home environment. All the material is performed acoustically, and throughout the CD we can hear the room itself, the air, and in quieter numbers the soft penetration of background talk. All of these elements produce a very intimate recording. Sadly, though, some of the songs’ performances fall short or flat. One of McDowell’s many attributes is his ability to create tension. His mastery of melody and rhythm, for which there are few equals, usually has time to be developed and carried through his performances. In Come And Found You Gone many songs sound truncated, rushed, or are cut off too soon, which could be a case of something perhaps a little too intimate. One could chalk this up to a tendency among many posthumous recordings, in which, for the sake of showcasing an early or less polished performance, a listener is allowed to hear a different or less-cured approach to a song or batch of songs. I wonder if the project was compromised by a limited recording value or if McDowell himself just began to grow a little distracted, bored or tired.

Don’t get me wrong--- a lack of industry polish is also a very welcome thing. I would think that this recording is only being released now because bigger, established labels may have passed on it. Not a shame at all, I say. It’s out now, and Devil Down's founder, Reed Turchi, should be commended for it. A captured night of tape in McDowell’s hometown of Como, Mississippi should demand the attention of a new and old fans alike. Unfortunately, for all the CD’s attention to the region’s invaluable musical legacy and traditions, the underlying anthropological aim to this CD is more a credit to the region and its customs than it is to a night of decent Fred McDowell recordings. A collection of photos within the CD package artfully displays the environment of The Hills (an area in northeastern Mississippi that McDowell both lived in and in whose musical traditions he was a product of), and liner notes supplied by Ferris, Luther Dickinson, and “eminent French blues scholar Vincent Joos” are by turns elegiac and informed pieces of a package intended to not only entertain but to educate its listeners as well.

At first I was a bit distracted by this. I thought, What should a live recording be but a document in and of itself? A live recording should effectively conjure a singular spirit whose existence takes its shape and sound from a body of music. As such, further listening and reading encouraged me to appreciate the effort Turchi has taken to release this recording. He’s obviously a very knowledgeable and avid fan of Fred McDowell, and he has commandeered three other astute fans to help him elaborate and present a labor of love. But I can’t help asking myself: Are there better, more resounding McDowell recordings in the world? Yes. Even so, I really don’t think Come and Found You Gone was meant to be presented as the very best. It is, above all, an evocation of a humble night in which listeners are invited to participate in an integral and enriching grasp of the Blues. We get all of the fundamental ingredients: the pain, the fear, the anguish; alternatively all the fun, humor, and abandon to be found in the Blues. This record is a friendly and highly respectful homage to a person whose status resides in a pantheon reserved for only the finest and most revered Blues artists of all time.

"Find My Suitcase" mp3

by Mississippi Fred McDowell, 1967.

available on Come And Found You Gone: The Bill Ferris Recordings

"The Boogie" mp3

available on Come And Found You Gone: The Bill Ferris Recordings

by Napoleon Strickland, 1967.

"Come And Found You Gone" mp3

by Mississippi Fred McDowell, 1967.

available on Come And Found You Gone: The Bill Ferris Recordings

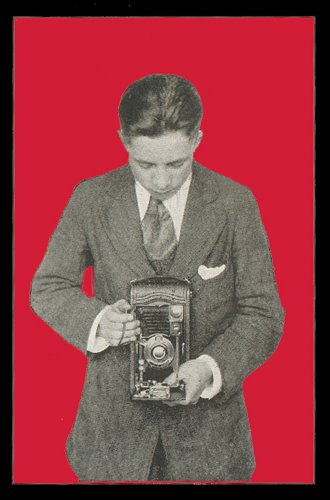

top photo: by Lee Friedlander

Mississippi Fred McDowell, 1960.

from American Musicians © 1998